It’s often said that translation is an art, not a science, and a series of videos on Youtube has popped up to prove it. Malinda Reese is the star of Google Translate Sings, a series begun when she decided to put the lyrics to “Let It Go” through multiple languages in a row on Google Translate and then sing the (virtually unrecognisable) results. Since then, she’s done all kinds of videos, ranging from “One Day More” from Les Misérables to “I’ll Make a Man Out of You” from Mulan. Here’s her latest video, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz…well, sort of:

Month: June 2015

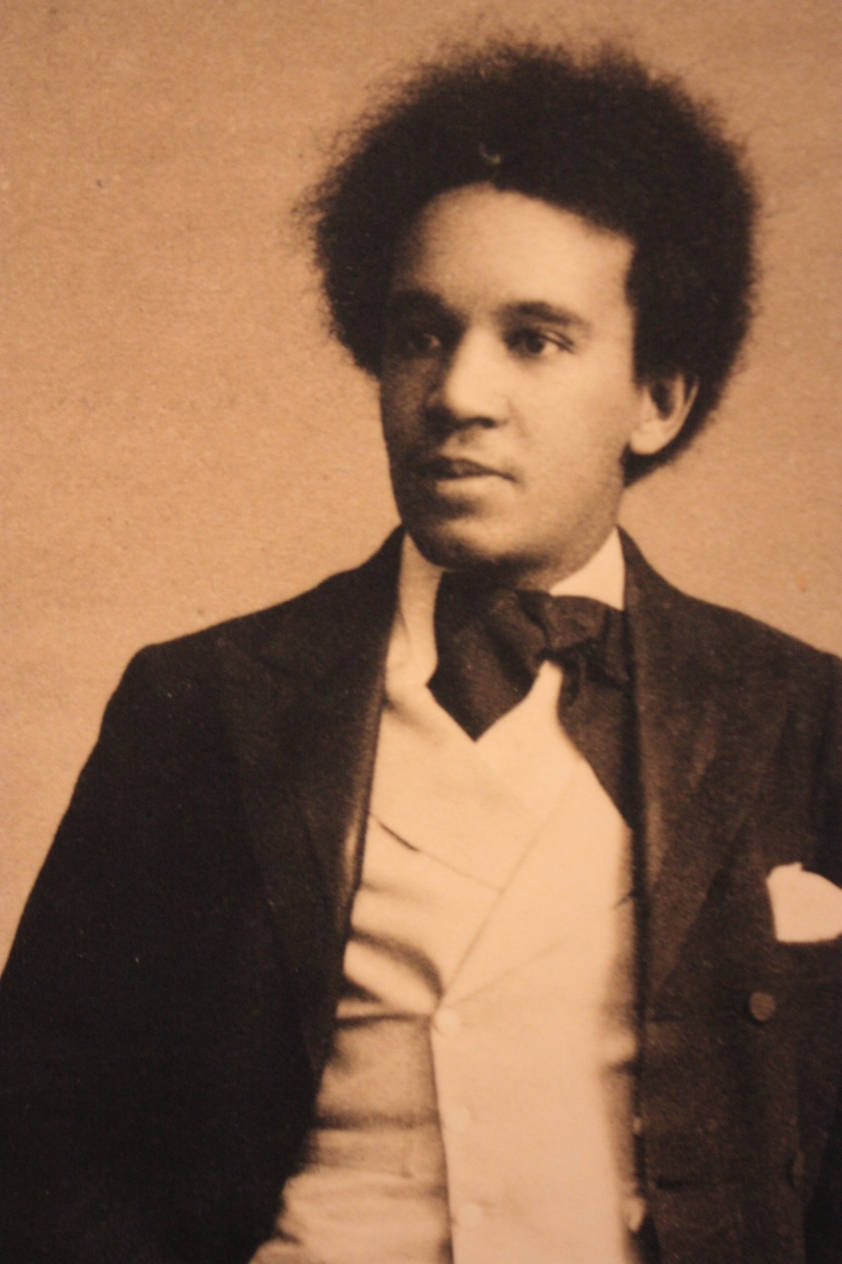

History Hunt: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

This week, we’re bouncing back to Britain and forward a decade to meet still another composer who succeeded in spite of constant prejudice: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

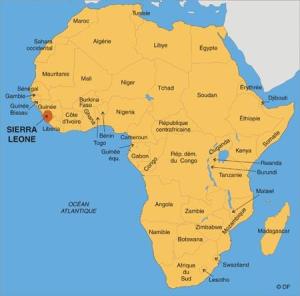

Coleridge-Taylor was born on August 15, 1875. (His name was originally Samuel Coleridge Taylor, but later in his life, when a publisher made a typo, he liked the look of Coleridge-Taylor so much, he kept it!) His father had been studying medicine in England, but not long after Coleridge-Taylor’s birth, he returned to his home of Sierra Leone. It was too difficult for him to work in England: few people in those days wanted to be treated by a Black doctor, no matter how skilled he was.

Coleridge-Taylor and his mother, who was white, stayed behind in England, and not long after he was born, his mother moved to Croydon.

It was here that Coleridge-Taylor’s good fortune began. While he had been born in one of the poorest areas of London, Croydon was a much better place to grow up for a young man–especially since this was where he began taking his first music lessons. His first music teacher was his grandfather, Benjamin Holmans, who taught him the basics of how to play the violin; when he was five, Joseph Beckwith started giving him formal lessons. He was also taught by Colonel Herbert A. Walters, whose choir he later joined when he was ten years old.

In addition to singing and playing the violin, Coleridge-Taylor was also a pianist. When he was fourteen, he finally managed to save up for a very cheap piano. It wasn’t much, but at least now he had an instrument to play on. Though it wasn’t his main instrument by any means, he kept up his practice all the same.

When Coleridge-Taylor was just fifteen, Colonel Walters introduced him to the head of the Royal College of Music, which was at the time a brand new music school. Luckily for him, he won a scholarship that made it possible for him to attend and he was soon going to school with students who would become some of the best known British composers of the late 19th and early 20th century.

His original intent, when he first started going to the school, was to study the violin. However, Coleridge-Taylor soon found his calling: composition. While he was still a violin student, he published his first composition, Te Deum. The next year, in honour of Colonel Walters, he published In Thee, O Lord, the first in a series of compositions. When he was seventeen, he officially became a composition student. Within a year, his works were being performed; within two, he was winning prizes. He also started conducting the Croydon Conservatory Orchestra in his hometown. It was a brave step: Coleridge-Taylor was known to be shy–so shy, in fact, that he might actually have hidden from everyone after the first performance of his compositions!

Still, even as he was being recognised for his tremendous talent, Coleridge-Taylor was facing the same racism and bullying that had been a part of his life since he was a schoolboy (and that would continue for the rest of his life). But, at the Royal College of Music, he was lucky enough to have friends to stand by his side. As Mike Phillips of the British Library Online reports:

“There is a typical and well-established story of his time at the RCM when [Coleridge-Taylor’s composition teacher,] Stanford, overhearing another student deliver a racial insult, rounded on the culprit and told him that Coleridge-Taylor had “more music in his little finger” than the other student had in “his whole body”.”

In addition to being shy as a young man, Coleridge-Taylor seems to have also held himself to high standards. Shortly after his graduation, he tried to burn a composition that his teacher hadn’t liked. Luckily for the musical world, a close friend of his grabbed it and saved it!

Fame as a composer found Coleridge-Taylor quickly: he was only twenty-three when he came into the spotlight. First came his Ballade in A Minor, which was a huge success at its debut and when it was performed at the prestigious Crystal Palace. Almost immediately afterward came an even greater success–Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. Coleridge-Taylor used the white poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, “The Song of Hiawatha,” as a foundation for his music. The poem was very popular at the time, even if it was a very inaccurate depiction of First Nations legends.

The British public as a whole loved Coleridge-Taylor’s composition–for some time, it rivalled Handel’s Messiah in popularity! Famous composer Sir Arthur Sullivan (of Gilbert & Sullivan), though he was very ill at the time, refused to miss its debut, saying, “I’m coming to hear your music to-night even if I have to be carried.” (Phillips)

The next year was a busy one for Coleridge-Taylor. With the success of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, the Royal Choral Society asked Coleridge-Taylor to compose a sequel, which he did within the year. He was also married to his sweetheart, Jessie Fleetwood-Walmisely, a pianist who was one of his schoolmates at the Royal College of Music.

Over the following years, Coleridge-Taylor was kept very busy. He composed, conducted, lectured on music, taught lessons, helped organise the first Pan-African Conference in London, started a newspaper with a friend (The African & Orient Review)–and became a father! He also started funding the Croydon Symphony Orchestra out of his own pocket when it ran out of money.

He had the opportunity to tour the United States three times, where he was extremely popular. In fact, the group that invited him in the first place was the Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society! He even got to meet President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House! And while racism in the United States during that time was an even bigger problem than in the United Kingdom, while Coleridge-Taylor was there, he was actually “allowed” to conduct white orchestras–something that was normally unheard of.

In spite of Coleridge-Taylor’s incredible popularity during his lifetime, it’s only recently that his music is being rediscovered. In fact, his opera, Thelma, was only found again in 2012 by Catherine Carr. I hope that in the years to come, we’ll start hearing more and more of Coleridge-Taylor’s music once more.

Here’s the last movement of his Petite Suite de Concert, “La Tarantelle Frétillante” (The Wiggling Tarantella):

If you’re enjoying the History Hunt series, why not drop me a tip or subscribe to me at Patreon? History Hunt will always be free–this is just an option for my readers to show their appreciation.

To Learn More (Sources):

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) by Mike Phillips

Black Mahler: The Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Story

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor on AfriClassical.com

A Note On Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Early Work at the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Foundation website

“I want to be nothing in the world except what I am – a musician.” (Discovering ‘Thelma’, Coleridge-Taylor’s only opera) at the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Foundation website

Royal College of Music at Wikipedia.org

The Song of Hiawatha at Wikipedia.org

Something New From Something Very Old

Drums have been around for as long as people have enjoyed hitting objects to make noise–so, in other words, for as long as people have been people. But that doesn’t mean that we’ve stopped working out new ways to make new noises!

Earlier this year, I was introduced to the Hang (or handpan, or spacedrum–there seems to be some debate about which name is best), which is a new type of drum barely fifteen years old. There aren’t many companies that make this new type of drum yet, and it seems they’re mostly in Europe. I’m hoping that will change, though, because boy oh boy do I want one!

History Hunt: Amy Beach

This week, we’re crossing the Atlantic Ocean to meet a composer who was working around the same time as Dame Ethel Smyth–but whose luck was much better.

Amy Beach was born Amy Marcy Cheney on September 5, 1867. Like many of the people we’ve met through the History Hunt series, her genius for music appeared early–very early. When she was only one year old, she had memorised forty songs and had learned not only to sing in tune, but to improvise sung music with her mother!

When she was three, she taught herself to read, and when she was four, she’d composed her first song, “Mama’s Waltz.” What was especially incredible about “Mama’s Waltz” (as well as two more pieces she wrote at the same time) is that all three were for the piano…but they were composed while she was visiting her grandparents, who didn’t own a piano. Upon Beach’s return from her visit, her mother was skeptical that her daughter had written anything at all. Beach told her that she’d heard the piano music in her head and went to play her compositions on the family piano to prove it!

Her mother, Clara Cheney, was a skilled pianist and singer in her own right, and she started formally teaching piano lessons to Beach when she was six. Beach gave her first recital when she was seven, and by the time she was eight, it was already clear that she was going to need lessons from professionals.

Unfortunately, while Europe was considered the best place to learn to play Western Classical music at that time, Beach’s parents couldn’t afford to send her. Instead, she learned as much as she could by going to a private music school in Boston, where she and her family had recently moved.

When she was fifteen, she published her first of over three hundred compositions, The Rainy Day. Later that year, just after she had turned sixteen, she gave her first professional performance at the Boston Music Hall. According to The Kapralova Society Journal, “The Boston correspondent of the New York Tribune reported that ‘she played with all the intelligence of a master.'” It was the first of a series of very successful concerts she gave until 1885.

It was during this period, in the first part of the 1880s, that Beach began to run into the sexism that Dame Ethel Smyth spent her whole life fighting against. While the majority of male composers would have been taught how to write music as soon as they showed a degree of talent, Beach was more or less left to figure it out on her own. She was lucky enough to study for a year with a composition teacher, Junius W. Hill, but that was the sum of her lessons.

Many people would have given up at this point, but not Beach. She wrote out compositions by famous composers from memory, then checked what she had written against a copy of the music. She went to concerts, listened intently, and then wrote down as much as she could remember from each part and once again checked what she had written. When she found untranslated essays on composition written in French, she sat down and translated them herself so she could learn from them!

As for her performances, while many reviewers praised her genius without feeling the need to say she played well “for a woman,” there were still those who clearly believed that she was some sort of an exception. Even after she went on hiatus from performing publicly, this kind of backhanded compliment continued to show up when people discussed her compositions.

When Beach married in 1885, when she was eighteen, her husband asked her to stop performing professionally, except for charity, and that only rarely. Even though he was a singer and must have understood how wonderful it is to share music with others, he wanted Beach to stay at home to run their household. It was a request that wouldn’t have been seen as extraordinary at that time, even if nowadays we know that he was being sexist and unfair.

However, unusually, Beach’s husband was actually supportive of her composing. He was very proud of her genius and used his position as a doctor and a lecturer at the famous Harvard University to promote her music. Along with Beach’s mother, he also helped her figure out what was working in her compositions and what wasn’t.

Also in 1885, she had a stroke of luck that Smyth would have been envious of: she met a publisher named Arthur P. Schmidt, who was determined to show that American women composers were writing just as brilliant of music as American men. They struck up a partnership that lasted for the rest of Beach’s life, and overall, Schmidt published more than two hundred of Beach’s compositions.

As Beach became known as a composer, she started receiving the same sort of sexist reviews as Dame Ethel Smyth did: if she wrote bold, powerful music, she was thought “unfeminine” (Gates) and unattractive. If she wrote quiet, delicate music, she was dismissed as being feminine and thus, according to the ideas of the day, unimportant.

However, unlike Smyth, when Beach grew in popularity, the reviewers stopped criticising the personality of the woman writing the music and learned to appreciate her compositions on their own merits. It was an extremely fortunate position shared by few women of her day.

Beach achieved several firsts before she was even thirty: her first large-scale composition, Mass in E-flat, became the first work by a woman by the Boston Symphony and the Handel and Haydn society; also that year, another of her works achieved a similar first with the Symphony Society of New York. She also wrote the very first symphony written by an American woman, her Gaelic Symphony. Its music was based on Irish Gaelic folk songs that Beach had heard and admired. Using traditional melodies in art music was a popular trend at that time, and Beach also went on to arrange music by Alaskan Inuit and First Nations composers, as well as African-American, Scottish, and southern European composers.

After the death of her husband and mother within seven months, Beach took a long break from music. A year after her husband’s death, in 1911, she left for Europe to continue her recovery, but in 1912, she began not only composing but performing publicly once more. She became hugely popular in Germany, and through her incredible music gifts, began to make people realise how wrong their prejudice against women was.

But in 1914, World War I broke out, and Beach needed to return home to America. Though she had to leave her successful career in Germany behind, for the rest of her life she remained a popular composer and artist in America and worked to give other American women the same musical opportunities she had.

While Beach was forgotten for decades after her death, determined History Hunters in recent years have begun to bring her back into the well-deserved spotlight. Like Hildegard of Bingen, Amy Beach is becoming one of our success stories–and thank goodness!

Below is one of Beach’s piano compositions, “Hermit Thrush At Eve, Op. 92, No. 1.” There’s a good selection of her music available on Youtube, including her Gaelic Symphony, so don’t forget to take a listen!

If you’re enjoying the History Hunt series, why not drop me a tip or subscribe to me at Patreon? History Hunt will always be free–this is just an option for my readers to show their appreciation.

To Learn More (Sources):

Mrs. H. H. A. Beach: American Symphonist by Eugene Gates in The Kapralova Society Journal

Amy Beach at Naxos.com

Amy Marcy Beach at the Encyclopædia Britannica

Amy Beach at the Library of Congress

Amy Beach: Quartet For Strings (In One Movement), Op. 89 at Music of the United States of America

Amy Beach at Wikipedia.org

Songs of Amy Beach at AllMusic (image source)

Incredible Kids: Honoka & Azita, Ukulele Stars!

I’m still learning about what school music is like in Ontario, but ever since I was finishing my music degree in my former home of PEI, a popular choice for Grade 6 music has been ukulele classes. I have a ukulele myself–a birthday present from my grandmother–although all I can manage at the moment are a few chords. (I need to practice more!) But, as is the case with the recorder, when all you hear are your fellow beginners, it can be easy to forget (or be completely unaware of) the potential of the instrument to make terrific music.

Listening to duo Honoka & Azita, though, I’m in no danger of that! The Hawaiian-born pair have been playing ukulele since they were eight and four, respectively, and are now sixteen and fourteen. And their talent is not to be believed:

They have more videos available on their Youtube channel, including a cover of the surf-rock hit “Wipe Out.” They’re definitely worth checking out!

History Hunt: Dame Ethel Smyth

This week on History Hunt, we’re staying in England and moving forward a few decades to meet a woman with many talents and a great deal of stubbornness: Dame Ethel Smyth.

Smyth was born on April 23, 1858, in London, England. Her mother, Nina Struth Smyth, was described later by her daughter as being “one of the most naturally musical people I have ever known.” (Gates) Her father, on the other hand, was the complete opposite: he despised artists of all types, thinking they were all immoral people (in spite of never having met a single artist in his life). He also was convinced that women should only be mothers, and the only place for them was at home.

Needless to say, adventurous Smyth didn’t agree with him at all. When she was introduced to classical music by one of her governesses when she was twelve, she knew exactly what she wanted to do with her life: she wanted to compose and make music just as beautiful as the composers who had gone before her. She would attend the Leipzig Conservatory, a music school in the German town of Leipzig, where many famous composers had lived and worked in the past.

Her father was extremely discouraging when she told her parents what she was determined to do, but Smyth held onto her dream. When she was seventeen, she started taking music and composition lessons–but not for long. Her father became convinced her music teacher was up to no good and cancelled the lessons. And when she was nineteen, open warfare between father and daughter began. Smyth locked herself in her room and refused to come out or speak to anyone until her father agreed to let her go to Leipzig…and at last, he gave in. Smyth had finally won.

But the Leipzig Conservatory wasn’t what Smyth had hoped for, and so she left after only a year to study with the composer Heinrich von Herzogenberg. It was during this time that she fell in love for the first time, with von Herzogenberg’s wife, Lisl.

It was also during this time that Smyth got her first taste of what was to become a lifelong battle for her. When she had arrived in Leipzig, Smyth had brought some of her compositions with her, hoping to find a publisher. What she found instead was the attitude that “Everyone knows women can’t compose.”

This wasn’t the only example of sexist thinking that Smyth ran up against, either. Later on, whenever she composed strong, forceful music, critics accused her of writing “like a man” and thought it made her “unattractive.” When she wrote delicate, soft music, critics dismissed her music as being “feminine” –as if being feminine were a bad thing! Few seemed to understand that these criticisms were nothing more than sexist nonsense, something that frustrated Smyth to no end.

Still, in spite of these barriers, while she was in Germany, Smyth had two of her works performed at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, a concert hall. One performance was when she was twenty-six and one was when she was twenty-nine. A few years later, after becoming reasonably well-known in Germany, she returned to England…where she had to start all over again!

It didn’t take her long, though, to gain a following in England in spite of her constant struggle against sexism. Her works began to be played at famous concert halls of the day: the Crystal Palace and the Royal Albert Hall–with a little help from her friend, Empress Eugenie of France!

Afterwards, Smyth composed her first opera, Fantasio, for a contest. On the advice of a friend, she submitted it under a male pen name, so she wouldn’t have to worry about sexism ruining her chances. Out of the 110 operas submitted, Fantasio placed in the top seven!

Her next opera met with even more success. In fact, it was performed at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House in 1903–the first opera written by a woman ever performed there! In fact, as of now, she’s the only woman to have a single work performed at The Met. That’s scheduled to change in the 2016-2017 opera season, when L’Amour de Loin by Kaija Saariaho is slated to be performed. Sexism, unfortunately, is not something confined only to the past.

Smyth went on to write four more operas–her most famous, The Wreckers, debuted three years later. But not long after that, Smyth’s attention turned to something very important: helping women earn the right to vote.

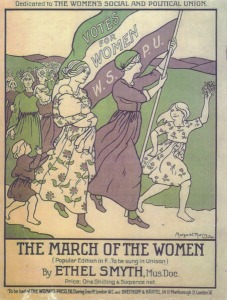

For most of Smyth’s life, women were not allowed to vote–they only fully gained the right in the United Kingdom in 1928, when Smyth was 70. But in 1910, Smyth fell in love with the cause of claiming this important right–as well as a leading figure in the fight, Emmeline Pankhurst. She became a fierce supporter, writing an anthem for the movement called “The March of the Women.”

She also went to jail for two months for breaking an opposing politician’s window! While in jail, she didn’t despair, but kept up her spirits and those of the other women who had gone to prison for fighting for their rights. In fact, when one of her friends visited her, it was to find Smyth conducting her fellow inmates in singing “The March of the Women” by leaning out of her cell window…using a toothbrush instead of a baton!

Sadly, later in life, Smyth went deaf, and so she could no longer compose. Instead, she turned to writing books. She wrote ten in all, as well as a large number of magazine and newspaper articles. For the rest of her life, she fought for the rights of her fellow female musicians and composers–a fight that continues to this day.

Listen below to “The March of the Women,” as well as the first movement of her Sonata for Cello and Piano in A minor, Op. 5:

If you’re enjoying the History Hunt series, why not drop me a tip or subscribe to me at Patreon? History Hunt will always be free–this is just an option for my readers to show their appreciation.

To Learn More (Sources):

Dame Ethel Smyth: Pioneer of English Opera, by Eugene Gates in The Kapralova Society Journal

Five facts about Dame Ethel Smyth, by Christopher Wiley on Oxford University Press’s blog

Ethel Smyth on Spartacus Educational.com

Dame Ethel Smyth: Composer, suffragette, sportswoman and resident of Woking on Exploring Surrey’s Past

Metropolitan Opera Adds Three Composers to New-Works Program, Commissions Operas by Thomas Adès and Osvaldo Golijov on Opera News.com

List of compositions by Ethel Smyth on Wikipedia.org

Women’s suffrage on Wikipedia.org

Competition, Collaboration, and Contortion

High up on my list of Favourite Things Ever would most definitely have to be this quartet performed by Salut Salon, which starts off as a “competitive” version of the presto movement of Vivaldi’s “Summer” from The Four Seasons, but soon turns into…well, you’ll see!

As much as it looks as if the performers aren’t getting along, the sheer amount of cooperation, choreography, and practice this would have taken to pull off the performance boggles the mind. Fantastic work, Salut Salon!

History Hunt: Mary Anne à Beckett

I’m back on the hunt this week with another British composer with not all that much information available. In fact, my sources can’t even agree on the spelling of her name!

Mary Anne (or possibly Mary Ann) à Beckett was born Mary Ann(e) Glossop on April 29, 1815, in London, England. Her mother was a singer whose parents escaped the French Revolution and who sang under the name Madame Feron. Her father was in charge of a series of several theatres in England and Italy. Not much is known about à Beckett’s childhood, but we do know she stayed at a convent in Avignon, France for a reasonably long period, and that it was during her family’s time in Italy that she studied music.

à Beckett composed a variety of music throughout her life, including a dozen vocal pieces and three piano works, but she’s best remembered for the three operas she and her husband, Gilbert Abbott à Beckett, wrote together. Agnes Sorrel was her first, written when she was only twenty, and it was later followed by Little Red Riding Hood, and The Young Pretender. à Beckett composed the music for all three operas, while her husband wrote the libretto, or lyrics, for the first two and another writer named Mark Lemon wrote the libretto for the third. While à Beckett’s music was well liked and praised in reviews, her husband and Lemon didn’t fare so well: the libretto for Agnes Sorrel was described as “cold, dull and comfortless” and Lemon’s writing in The Young Pretender was called “as dreary a production as it is possible to imagine in any work professing to be a drama.” (Wikipedia) Yikes!

Though à Beckett was a conductor as well as a composer, it seems she was shy. She was offered the opportunity to conduct the first performance of Agnes Sorrel, but she turned it down. Later in her life, she published a collection called The Music Book, along with some of her fellow (male) British composers, and after that, as is so often the case with forgotten composers, she fades from history.

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to locate any of à Beckett’s music in a readily available listening format. If any of my readers could lend me a hand, I’d be tremendously grateful!

If you’re enjoying the History Hunt series, why not drop me a tip or subscribe to me at Patreon? History Hunt will always be free–this is just an option for my readers to show their appreciation.

To Learn More (Sources):

A’Beckett, Mary Anne (1817 – 1863), composer on Grove Music Online

Mary Ann à Beckett at Victorian English Opera

Mary Anne à Beckett at Wikipedia

Twelve Doctors and a TARDIS-Blue Piano

Here’s a treat for fans of the long-running British scifi series Doctor Who! Composer and pianist Sonya Belousova plays an enthusiastic rendition of the TV show’s theme song while alternating between versions of the costumes of all twelve actors (to date!) who have played the Doctor.

I can’t imagine the amount of practice and number of times she had to play the piece to make such a seamless video. That’s a lot of hard work, but did it ever pay off!