This week, we’re continuing our celebration of American artists and moving forward in time to meet someone who, for a time, shared a building with another History Hunt-featured artist, Marian Anderson!

Robert Keith McFerrin, Sr. was born on March 19, 1921 in Marianna, Arkansas, one of eight children! Like many of the musicians showcased on History Hunt, McFerrin’s love of music began early. As a boy, he joined his church choir and sang soprano, and he was also a talented whistler.

McFerrin’s father was a strict Baptist minister, he didn’t want McFerrin to learn any music but gospel songs. McFerrin respected his wishes and took advantage of the opportunities available to him, which included joining two of his siblings and participating in a travelling church music trio when he was thirteen.

But as much as his parents wanted to keep their son near, they knew that McFerrin would have a better chance at a good education elsewhere. And so, when McFerrin finished Grade 8, he went to live with his aunt and uncle in St. Louis, Missouri.

Despite McFerrin’s great musical skills, his original plan was to become an English teacher. He changed his mind, however, when he joined the choir in high school. His wonderful voice so impressed the choir director, Wirt Walton, that his teacher took him on as a private student for the next four years.

Walton had just as strong opinions about the music McFerrin should sing as McFerrin’s father had. Ironically, though, the music Walton didn’t want McFerrin singing was pop music…and gospel! McFerrin, however, recognised the importance of the music he’d grown up singing:

“I believe that my singing of gospel music and hymns strengthened my voice and gave me the ability to sustain my singing and endure whatever role I was assigned to sing. The study of voice only served to secure musicianship and aid in the control of my voice.”

As his high school graduation grew near, so he could afford to study music at university, McFerrin put on his first solo recital. He used the money he raised to go to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. However, it seems that the university wasn’t a good fit for McFerrin, as he left after a year. He soon won a scholarship to study at Chicago Musical College instead, and within a year, he’d won the singing competition at Chicagoland Music Festival!

Before he could finish his studies at Chicago Musical College, though, the United States joined World War II, and in 1943, McFerrin was called to fight. He was very lucky indeed, as he survived unharmed and came back to finish his degree a year after the war ended, in 1946.

When he graduated, McFerrin moved to New York and began studying with Hall Johnson, who was a well-known musician in McFerrin’s day. He soon fell in love with fellow singer Sara Copper; they married within a year of McFerrin’s arrival in New York.

It was here in New York that McFerrin’s career as a singer really began. In 1949, when he was 28, he got his first part on Broadway in Lost in the Stars. It wasn’t a large part, but it led to more–a lot more. He won a scholarship to the Tanglewood Opera Theatre and starred in the opera Rigoletto by famous composer Giuseppe Verdi. He also was one of the musicians in the first opera performed by a major American opera company, Troubled Island, by William Grant Still.

From here, McFerrin’s popularity only continued to grow. But in spite of this, when his manager suggested he audition for the prestigious Metropolitan Opera during their “Auditions of the Air” competition, he decided against it. He didn’t feel ready to join something so big. His manager knew he could do it, though. She was so convinced, she filled out the audition form, signed it as “Robert McFerrin,” and mailed it off. Imagine McFerrin’s surprise when he got a phone call saying he’d won the right to audition for something he’d never applied to!

Even though he wasn’t sure he was good enough, McFerrin decided to accept the audition. It was a good thing he did: he placed first out of everyone, becoming the first African-American to do so. That earned him yet another scholarship to Kathryn Turney Long School, where he learned stage skills like fencing and ballet.

Usually, winners of the Metropolitan Opera’s competition earned a contract and six months’ training. McFerrin, however, received over a year of training–but no contract. Fortunately, McFerrin didn’t mind and was glad to learn what he could.

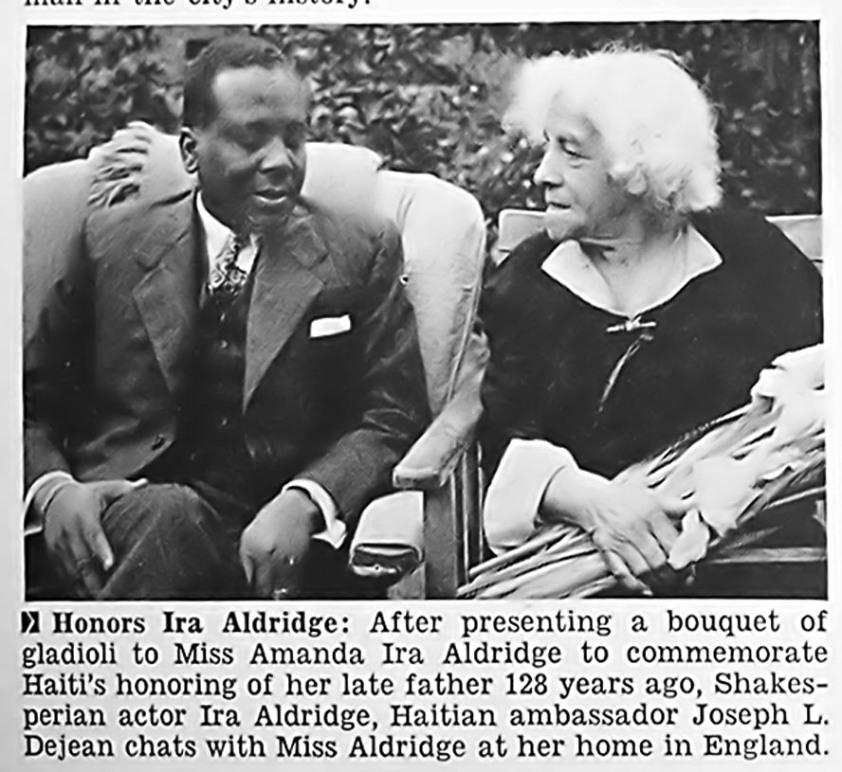

In January 1955, McFerrin and Marian Anderson became the first African-Americans to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. Anderson performed first, and McFerrin followed three weeks later. This wasn’t the only way the two were connected–as mentioned earlier, the two shared a building for a time. McFerrin lived on the ninth floor and Anderson on the tenth. Sara Copper, McFerrin’s wife, would even occasionally meet Anderson in passing (and from the sounds of things, was pretty starstruck about it!).

Performing at the Metropolitan Opera wasn’t all that McFerrin did during this period. On a European tour in 1956, McFerrin became the first African-American to sing at the opera house Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, Italy. The next year, when he was 37, he and his family moved to Hollywood so he could provide music for the film version of Porgy and Bess (the opera that brought Ruby Elzy fame).

When the filming was finished, McFerrin had a difficult decision to make. Although it had been important for him to join the Metropolitan Opera at the time, the racism of the 1950s was severely limiting his roles. At this point, he’d sung in only one opera every year, and never in a leading role. And so he quit his job at the opera to further his career in Hollywood.

He and Sara Copper began their own studio and he taught there for the next fifteen years, with some exceptions–such as when he was hired to teach in Finland! He and Copper eventually divorced, and McFerrin moved back to St. Louis. He kept singing for the rest of his life. In fact, one of his notable later performances was when he was 72. He was the guest singer for the St. Louis Symphony, which was conducted by none other than his son, who had become a famous musician in his own right!

Below is a recording from 1956 of one of McFerrin’s performances with the Metropolitan Opera, where he played the role of King Amonasro, the father of the title character, Aida.

If you’re enjoying the History Hunt series, why not drop me a tip or subscribe to me at Patreon? History Hunt will always be free–this is just an option for my readers to show their appreciation.

To Learn More (Sources):

Robert McFerrin at Afrocentric Voices in Classical Music

Robert McFerrin Sr. at The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

McFerrin, Robert Keith, Sr. at BlackPast.org

Robert McFerrin Sr.; Was First Black Man to Sing With the Met via the Washington Post

Singer Robert McFerrin, father of Bobby, dies on Today.com

Opera singer who broke racial barriers honored on Lawrence Journal-World

Robert McFerrin, Sr. at Encyclopædia Britannica

Robert McFerrin at Wikipedia.org

Aida at Wikipedia.org

Robert Mcferrin at Fine Art America (image source)