This week, we’re heading across the Atlantic Ocean to meet a composer who never stopped learning and trying new things throughout her very long life!

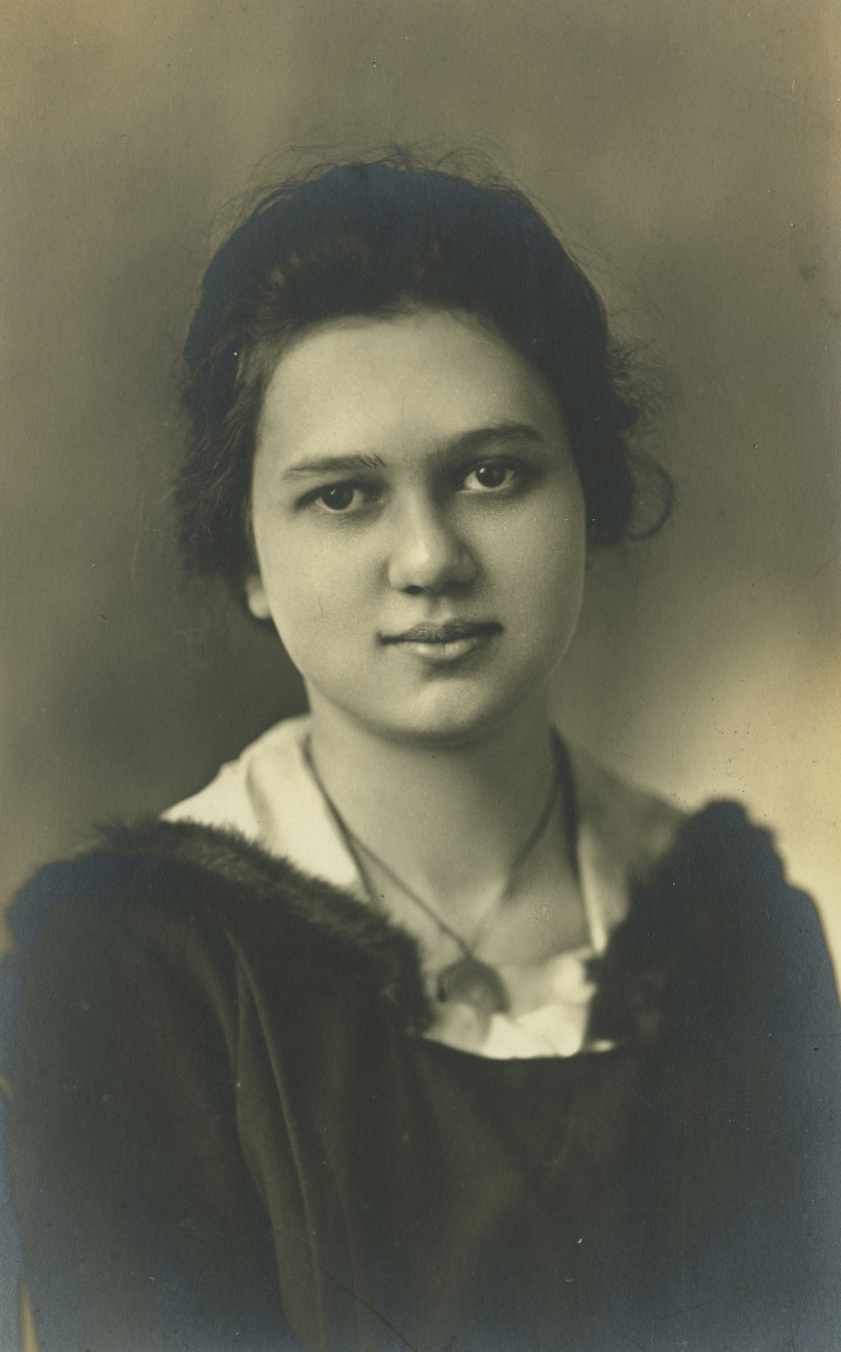

Germaine Tailleferre (born Germaine Taillefasse) was born on April 19, 1892 in Saint-Maur-des-Faussés, France. Like many of the composers and musicians we’ve met in this series, Tailleferre was interested in music from an early age and her interest was encouraged by her mother.

Unfortunately, as has also been the case far too often in History Hunt, Tailleferre’s father didn’t believe that becoming a composer was a “proper” thing for his daughter to do. It was up to Tailleferre’s mother to teach her how to play the piano and to encourage her daughter when she first began composing.

Tailleferre was only twelve when she went to study at the Paris Conservatory, without her father’s blessing or support. Two years later, when she won a prize for skill in solfège, her father started to think that maybe he had been wrong. But by then, Tailleferre had learned she could depend on herself just fine. Later, she changed her name from Taillefasse to Tailleferre, and continued with her studies.

By the time she was twenty, Tailleferre joined the active musical community in Paris and began studying orchestration. She spent the next three years winning first place in various competitions at the Paris Conservatory, for harmony and counterpoint, composition, and either accompaniment or keyboard harmony (sources disagree).

Between 1917 and 1918, Tailleferre’s circle of artist and musical friends expanded greatly. She was invited to participate in the first concert of the group “Les nouveaux jeunes” (“The New Young People”) after her piece for two pianos “Jeux de plein air” (“Outdoor Games,” or “Games in the Open Air”) was heard by one of the group members. Two years later, when Les nouveaux jeunes became “Les Six” (“The Six”), she was the only female member.

Les Six were considered some of the most important composers in France at the time. Although they didn’t actually compose much music together, they were leaders in composition and great friends, to the point where their children apparently still get together sometimes.

When Tailleferre was thirty-three, she married an American cartoonist known for his caricatures and moved to New York. Unfortunately, her new husband was of a similar mindset to Tailleferre’s father; he even went so far as to order her not to compose music for the movies of their friend, famous actor Charlie Chaplin.

Fortunately, Tailleferre had the opportunity to work on movie music after her divorce, working between the years 1931 and 1933. She also wrote an opera in 1931, although only the overture still survives. Even though she once again married a man who disliked the idea of women being professional composers in 1932, this time, Tailleferre didn’t let his disapproval slow her down. She kept on composing all throughout the 1930s and met with great success.

When World War 2 broke out, Tailleferre stayed in France for as long as she could, but as was the case with many composers during this time, she, her family, and her sister were forced to leave their home. They travelled first to Spain, then to Portugal, before finally arriving in the United States. With a growing daughter, Tailleferre didn’t have much time to compose, though when she went home to France a year after the war ended, she was able to work on her music more often. She worked in both film and radio music, as well as writing music on her own.

During the 1950s, Tailleferre briefly joined other composers who were experimenting with new musical techniques to break away from the traditions of Western Classical art music. In the end, though, she decided she preferred other sounds. She continued to write film music and opera, later worked as an accompanist to a dance studio, and, when she was 84 years old, she started teaching!

Throughout her long life, Tailleferre never stopped composing or reworking her old compositions. She proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that you’re never too old to stop learning.

Listen below to “Romance,” a beautiful piano piece Tailleferre wrote when she was only twenty-one!

If you’re enjoying the History Hunt series, why not drop me a tip or subscribe to me at Patreon? History Hunt will always be free–this is just an option for my readers to show their appreciation.

To Learn More (Sources):

Germaine Tailleferre on Classical Music Now (English, French. Please note the English translation is somewhat flawed and occasionally inaccurate.)

Tailleferre Germaine on Musicologie.org (French)

Germaine Tailleferre on Sinfini Music

GERMAINE TAILLEFERRE, WROTE MUSIC AS MEMBER OF LES SIX at The New York Times

Germaine Tailleferre on AllMusic.com

Germaine Tailleferre on Naxos.com

Germaine Tailleferre on Wikipedia.org (English, French)