This week on History Hunt, we’re back four hundred years in history to meet another composer whose popularity is beginning to take off again–even if we don’t know all that much about her.

Barbara Strozzi was born in 1619 in Venice, Italy, a city built upon the water!

We’re not completely sure of her birthdate–we only know she was baptised on August 6. She also was called Barbara Valle at this point in her life; she didn’t start using the name “Barbara Strozzi” until later.

Strozzi was adopted, growing up in the family of Isabella Garzoni, who was a servant, and Giulio Strozzi, a poet (who may or may not have been her birth father). She learned from one of the greatest composers in the new genre of opera, Francesco Cavalli and was so successful at her lessons, she had her first (but not last!) music book dedicated to her when she was only sixteen.

Two years later, she became the host of a musical discussion group, the Accademia degli Unisoni, or “Academy of the Like-Minded” (which is also a pun on the musical term unisono). She performed in the group as a singer, answered composition challenges put to her by other group members, judged debates, and organised which topics the members would discuss. This was extremely unusual for a woman of Strozzi’s day, especially a young woman. According to the beliefs of that time, women were not supposed to be leaders, especially not of men! But Strozzi didn’t listen, and even though some sexist people said some very rude things about her, she kept leading the group.

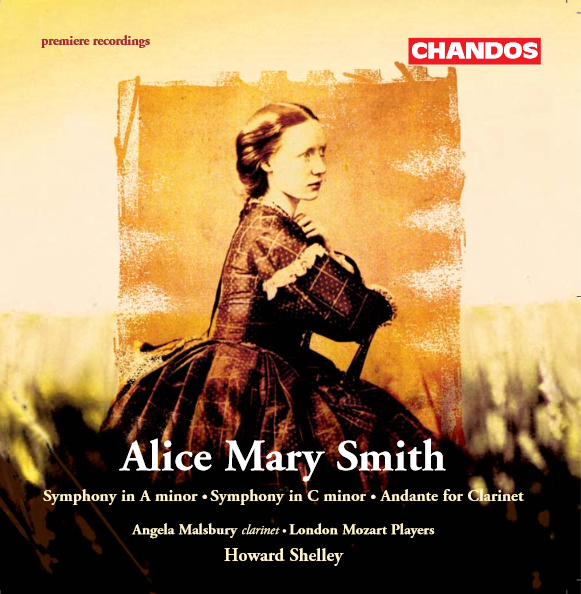

Something else Strozzi did that women of her day weren’t “supposed” to was compose–and she composed a lot! She published her first collection of madrigals (a type of vocal music) when she was twenty-five, and over the next twenty years, posted seven more books of her compositions. Almost all of them survive; only the fourth has been lost. Overall, she composed about 125 pieces–a solid output indeed.

After 1665, when she wrote music for the Duke of Mantua, Strozzi mostly drops out of sight of history. What she did during those years is unknown, but I hope she continued composing and singing for the rest of her life!

Below is an example of one of Strozzi’s compositions, “Amor dormiglione”:

If you’re enjoying the History Hunt series, why not drop me a tip or subscribe to me at Patreon? History Hunt will always be free–this is just an option for my readers to show their appreciation.

To Learn More (Sources):

Barbara Strozzi at Encyclopædia Britannica

Barbara Strozzi, “virtuosissima cantatrice”: The Composer’s Voice, by Ellen Rosand

Barbara Strozzi at AllMusic.com

Strozzi, Barbara at Encyclopedia.com (Note: References to mature subject matter in the link.)

Barbara Strozzi at Wikipedia.org