This week (well…it was supposed to be last week, but I had a ton of errands), we’ll be meeting our second Canadian of History Hunt, someone who actually lived fairly near me! It was a really neat discovery for me, and I’m planning on going out of my way to introduce my music students to him as soon as I can track down some of his works.

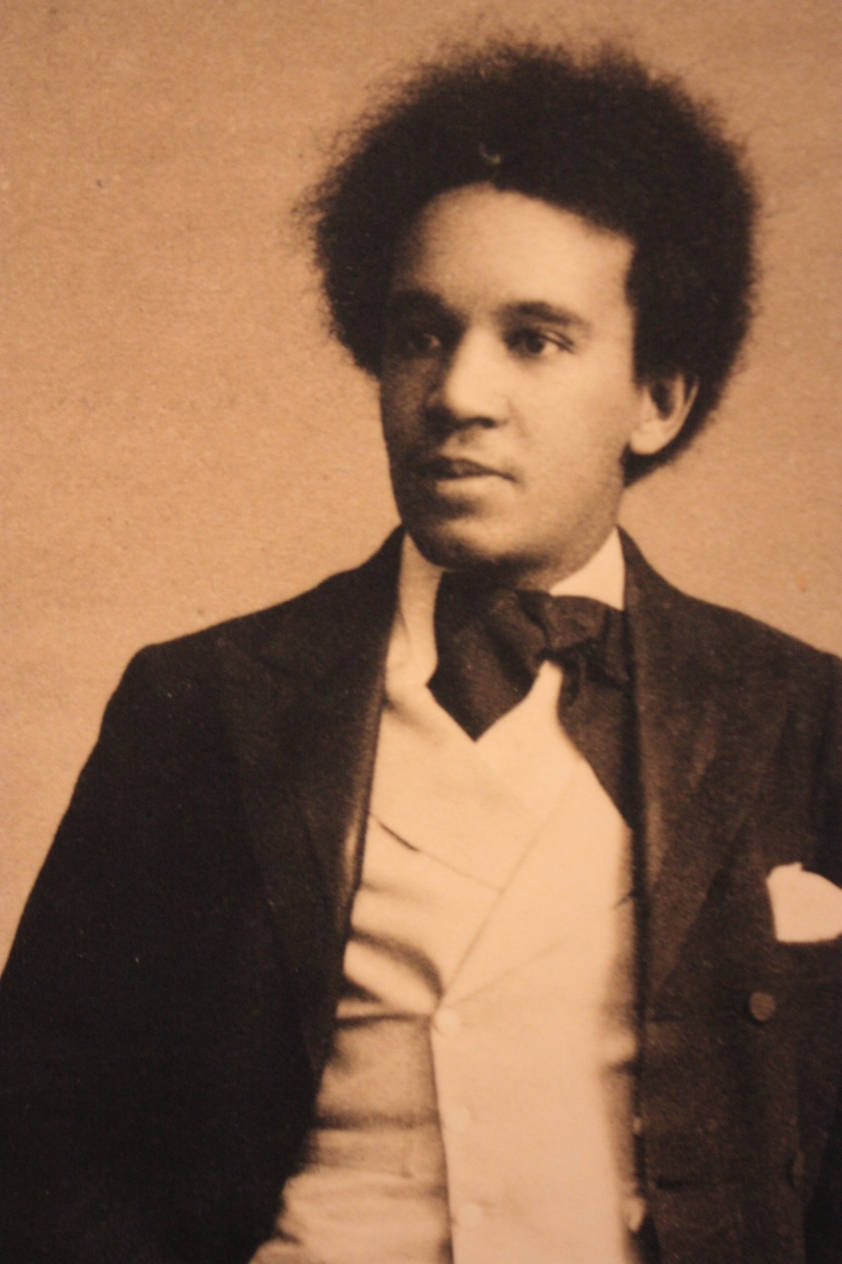

Robert Nathaniel Dett was born in Drummondville (now a part of Niagara Falls), Ontario, Canada on October 11, 1882.

Ontario, Canada, birthplace of R. Nathaniel Dett

At first, Dett’s musician parents didn’t realise that their youngest son had inherited their gift, but that was soon to change. While two of his older brothers were receiving piano lessons, Dett began to copy them. He played their pieces–but without the sheet music they were using. When his brothers’ teacher found out, she was so impressed that she started teaching him for free!

When Dett was eleven, his family moved to the United States side of Niagara Falls. There, he continued his piano lessons and later, around when he was fourteen, he took a job as a bellhop at a local hotel. When he had the time, he would play the piano located in the lobby, which earned him more than a few fans.

The next year, in 1897, Dett made a decision. While he was setting up chairs in the hotel parlor for a visiting bass singer (who had actually been his Sunday School superintendent), he told himself that the next time he moved chairs, it would be for his own recital. Sure enough, later that summer, he was able to put on a piano recital in the same hotel parlor.

When he was sixteen, Dett became church organist at a church on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls. In 1901, Dett began studying at the Oliver Willis Halstead Conservatory of Music; two years later, he quit his job as church organist to join the Oberlin Conservatory of Music. There, he majored in both piano and composition, which would have been a tremendous amount of work. It also would have been expensive, but luckily, when Dett gave a benefit concert after his first year to raise money for his classes, one of the attendees was so impressed that he promised to help him pay for his lessons.

While Dett was at Oberlin, he heard a performance of Antonín Dvořák’s American quartet that changed the course of his life. This work for strings was composed using traditional folk songs, and as Dett listened, he remembered his grandmother, who had sung songs written by African-Americans while enslaved. Dett had never been comfortable with the reminders of such a terrible time those songs brought. But now, he became determined to keep the memory of these songs alive, so they wouldn’t fade away.

In 1908, Dett graduated from Oberlin, holding a Bachelor of Music degree with honours. He was the first Black person to earn this degree at Oberlin. That wasn’t the last time Dett studied music, though: he earned degrees and honourary degrees from universities all over the United States, including the highly prestigious Harvard University. By far, Dett’s biggest learning trip was to Paris, France, later in his life. There, he studied with Nadia Boulanger, the older sister of last week’s History Hunt composer, Lili Boulanger.

After Dett’s graduation, he began teaching at Lane College in Jackson, Tennessee. In 1911, he showed he was a man of many talents by publishing a book of poetry he dedicated to his mother. He spent the next few years teaching at two more universities and studying how to teach choirs, and then, in 1914, he gave two piano recitals that cemented his reputation as a composer and a pianist–one of which was at the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Club in Chicago, Illinois. (This club was named after a previously featured History Hunt composer, who you can read about here.) He also entered a composition contest that same year put on by the Music School Settlement of New York and came second.

During World War I, Dett wrote music to keep up the spirits of both Canadians and Americans alike. He also got married, in 1916, to Helen Elise Smith, who was the first Black person to graduate from the Damrosch Institute of Musical Art (which later became part of the famous Julliard School of Music).

After the war, Dett founded the National Association of Negro Musicians in 1919, and was its president between 1924 and 1926. The next year, he published an essay in four parts called Negro Music, which was an analysis of the state of Black folk songs and how they might best be preserved. This essay won him a Bowdoin Prize from Harvard. These prizes are “some of Harvard’s oldest and most prestigious student awards” (Harvard); winning one was very significant indeed. He also won a Francis Boott prize from Harvard in the same year, this time for his composition “Don’t Be Weary, Traveller.” And, on top of that, later on, one of the groups to commission compositions from him was the TV station CBS, who asked for two separate symphonies!

After teaching at numerous universities, Dett settled at Hampton Institute in Virginia. There, he became the university’s first Black Director of Music by 1926 and united the university choir with local singers. With Dett at its head, the resulting choir went on numerous tours all across the United States and even to Europe and became very popular indeed. They performed in famous venues such as Carnegie Hall and Constitution Hall–the very same location that, eight years later, would refuse to allow Marian Anderson to perform for racist reasons. (See my History Hunt post on Marian Anderson for more information.)

Dett’s determination to preserve and help Black traditional music grow lives on even today. The Nathaniel Dett Chorale states on its website that it “is Canada’s first professional choral group dedicated to Afrocentric music of all styles, including classical, spiritual, gospel, jazz, folk and blues.” Dett would have been proud indeed.

Below is one of Dett’s most popular pieces from the suite In the Bottoms, “Juba,” which is based on traditional Black music and dance.

If you’re enjoying the History Hunt series, why not drop me a tip or subscribe to me at Patreon? History Hunt will always be free–this is just an option for my readers to show their appreciation.

To Learn More (Sources):

R. Nathaniel Dett at AfriClassical.com

R. Nathaniel Dett at Afrocentric Voices In “Classical” Music

Nathaniel Dett at The Canadian Encyclopedia

Roots and The Chorale at The Nathaniel Dett Chorale

Nathaniel Dett at Black History Canada

Robert N. Dett at the African American Registry

Dett, R. Nathaniel at BlackPast.org

R. Nathaniel Dett’s Views on the Preservation of Black Music by Jon Michael Spencer

Robert Nathaniel Dett Facts at YourDictionary

Bowdoin Prizes for Undergraduates at Harvard University

Dett Wins Francis Boott Prize at The Harvard Crimson

Juba dance at Wikipedia.org

R. Nathaniel Dett at Wikipedia.org (Image Source)